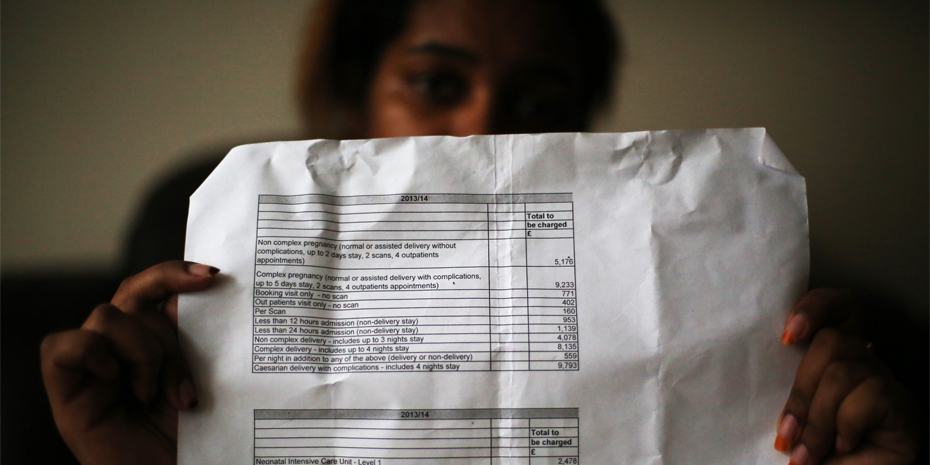

“I am a lesbian. I had a forced marriage which is why I’m pregnant. I had to flee for my life. At the hospital they gave me an estimate for the cost of my delivery of €12 000.”

Photo from Giorgos Moutafis

Since 2006, the MdM International Network Observatory on access to health care has carried out multicentre European surveys during face-to-face medical and social consultations with people facing multiple vulnerability factors in health (most of them migrants). MdM collects data on social and health characteristics, care needs and barriers to accessing care, in order to raise awareness among stakeholders and bring about positive changes in laws and practices.

An impressive range of international texts and commitments exist to ensure people’s basic and universal right to health.

However, many European countries have set legal and administrative barriers to care. Undocumented migrants are hit first, whether they are European Union (EU) migrant citizens or third-country nationals, often along with asylum seekers and destitute nationals. These restrictions on care often also apply to pregnant women and children. Data collected by MdM in 2014 – relating to 23 040 people in 25 cities in Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey(1) and the United Kingdom – demonstrate persisting gaps in access to health care (1).

Pregnant women involved in MdM programmes face multiple vulnerabilities. A large majority had no health care coverage (81.1%); over half of them had not had access to antenatal care prior to engaging with MdM; 67.8% restricted their movements for fear of arrest (an additional barrier to accessing care); and one third declared that they never or rarely had someone they could rely on in case of need. Personal health reasons for migrating were cited even less frequently than among all MdM patients (0.8% versus 4.0%), which reflects the absence of any push factor for migration related to their current pregnancy.

Nearly half of pregnant women who had minor children were living apart from one or more of them. They reported considerable emotional strain, including anxiety, guilt and a sense of loss, and they are at greater risk of depression. In addition, an overwhelming majority of patients (84.4%) questioned on violence reported they had suffered at least one violent experience, whether in their country of origin, during their journey or in the host county. These people need care and safe surroundings instead of living, too often, in ditches and slums, in fear of expulsion.

Only half of the pregnant women knew their HIV, hepatitis B or hepatitis C status when they arrived under the MdM programme and, of these, 14.3% were HIV positive, 11.1% tested positive for hepatitis B and 2.8% for hepatitis C. In addition, 67.1% of the women wished to be screened for one or the other of these viruses, but 34.3% did not know where they could go for the test.

Children of asylum seekers and refugees only have the same rights to health care as nationals in six of the surveyed countries. In most countries, children of undocumented migrants face legal barriers to accessing care and vaccination. As a consequence, only 42.5% of the children seen in MdM consultations were immunized against tetanus and, even worse, only 34.5% against measles, mumps and rubella viruses (that is, far fewer than among the general population).

EU countries and institutions within them must offer universal public health systems built on solidarity, equality and equity (rather than profit-making rationale), open to everyone living in Europe. They should ensure immediately that all children residing in Europe have full access to national immunization programmes and to paediatric care. Similarly, all pregnant women must have access to termination of pregnancy, antenatal and postnatal care and safe delivery.

Almost 100 European-level and national institutions, along with professional and civil society organizations endorsed the Granada Declaration in April 2014 (2), showing their deep attachment to the principles of ethics, human rights, and care for those most in need. They reject all instrumentalization of health care policies in the vain hope of limiting migration and/or public deficits.

Together with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Lisbon on the rights of the patient (3), MdM will continue to provide appropriate medical care to all people, without discrimination. MdM refuses all restrictive legal measures to alter medical ethics and exhorts all health professionals to take care of all patients, whatever their administrative status and existing legal barriers.

(1) In Istanbul, Turkey, the nongovernmental organization collecting data was L’Association de solidarités et d’entraide aux migrants (ASEM), an MdM partner.

Nathalie Simonnot, Frank Vanbiervliet, Doctors of the World (Médecins du monde, MdM) International Network

Cécile Vuillermoz, Dr Pierre Chauvin, Department of Social Epidemiology, Pierre Louis Institute of Epidemiology and Public Health (Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (INSERM) – University Pierre et Marie Curie (UPMC), Sorbonne Universities Group)

Click here to read the article on the World Health Organization site

References

|

1) Chauvin P, Simonnot N, Vanbiervliet F, Vicart M, Vuillermoz C. |

Capture-couverture |

2) Granada declaration. Utrecht: European Public Health Association; 2014 (http://www.eupha.org/repository/sections/memh/Granada_Declaration.pdf).

3) WMA Declaration of Lisbon on the rights of the patient. Adopted by the 34th World Medical Assembly, Lisbon, Portugal, September/October 1981; amended by the 47th WMA General Assembly, Bali, Indonesia, September 1995; editorially revised by the 171st WMA Council Session, Santiago, Chile, October 2005; reaffirmed by the 200th WMA Council Session, Oslo, Norway, April 2015. Ferney-Voltaire: World Medical Association; 2005 (http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/l4/).